what was the significance of opposition to the stamp act?

In 1763, colonial Britons historic victory over France in the 7 Years War. In Boston, proud citizens of the newly-enlarged empire lit bonfires, rang church building bells, mustered the militia, and toasted "loyal healths."[1] In 1764, celebration turned to condemnation as Britain began taxing American colonists to pay for their defence. The Sugar Act promised to inflict economic misery and the tyranny of taxation without representation.[2] Prime number Minister George Grenville was just beginning to brand Americans contribute their off-white share.

James H. Stark, "The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution" (1907)

Creating the Stamp Human action

In the summer of 1763, Grenville contemplated a colonial postage tax, a common grade of British taxation dating to 1694. Legal documents, bookish degrees, appointments to office, newspapers, playing cards, and dice carried an embossed Treasury stamp to bear witness payment. While British officials considered colonial stamp taxes in 1722, 1726, 1728, and 1742, they never usurped colonial responsibility for internal taxes.[iii]

Grenville addressed Parliament on March 9, 1764, intent on securing advance support for the unwritten stamp neb. He expressed hope "that the power and sovereignty of Parliament over every role of the British dominions, for the purpose of raising or collecting any tax, would never be disputed." The next solar day, Secretary of the Treasury Thomas Whately introduced colonial revenue-raising resolutions, including the Carbohydrate Act (passed April five, 1764). The fifteenth resolution—a stamp tax—was deferred for a year.[4]

As the prospect of a stamp taxation hung in the air, Grenville offered to let the provinces to "among themselves, and in modes best suited to their circumstances, raise a sum acceptable to the expense of their defense."[five] However, this offer was, equally historian Edmund Morgan observed, "nothing more a rhetorical gesture…to demonstrate his own benevolence." In a meeting with colonial agents on May 17, 1764, Grenville brushed aside questions about suitable forms of colonial cocky-taxation. Instead, he asked them to agree in advance to Parliament's right to tax the colonies, earlier they had seen a completed stamp pecker. Neither he nor the Secretary of State for the Southern Section ever made a formal offer to colonial governors or legislatures well-nigh acceptable colonial alternatives.[half dozen] As Benjamin Franklin observed later, Grenville was "besotted with his Stamp Scheme..."[7]

Four days afterwards, Parliament took upwardly the postage pecker. Charles Townsend described Americans as "Children planted by our Care, nourished upward by our Indulgence…and protected past our Artillery" who should be willing to "contribute their mite [small sum of coin]" to relieve Britain of its heavy debt. In severe opposition to this statement, Colonel Isaac Barré thundered:

They planted by your Care? No! your Oppressions planted em in America…They nourished past your indulgence? They grew past your neglect of Em…They protected by your Artillery? They have nobly taken upwardly Artillery in your defence… [8]

Despite Barré'south words, both Townshend and Barré agreed that Parliament had the authority to tax the American colonies. Grenville and Parliament invoked a long-standing dominion that Parliament would not have citizen petitions confronting coin-related bills, ensuring quick passage of the bill. The Stamp Act passed by a vote of 245 to 49 in the Business firm of Commons and unanimously in the House of Lords. Enacted into law on March 22, 1765, the Stamp Act would have issue on November ane.[9]

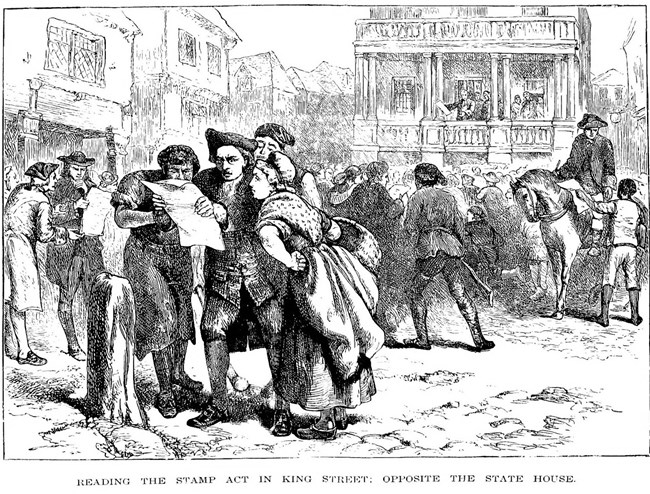

Boston printer John Boyle noted the inflow of the Postage Act on May 14, 1765: "Capt. Jacobson arrived here from London, has bro't over the Human action for levying certain Postage stamp-Duties in the British Colonies…"[10] Though the Stamp Act expected to bring merely a minor almanac acquirement (£60,000), it required payment in specie (difficult currency, such every bit golden or argent). Business organization arose amidst colonists who did not have access to hard currency, and they braced for disaster as reports, rumors, and contradictory paper accounts continued to swirl.[11]

Economical Impact of the Postage Act

Daniel Dulany, attorney and fellow member of Maryland's Proprietary Council, published "Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies…" in 1765. Although the pamphlet focused on the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation, Dulany likewise summed upwards the Stamp Deed's detrimental economic furnishings:

…for they [stamp duties] volition produce in each Colony, a greater or less Sum, not in proportion to its Wealth, but to the Multiplicity of Juridical Forms, the Quantity of vacant Land, the Frequency of transferring Landed Holding, the Extent of Paper Negotiations, the Scarcity of Money, and the Number of Debtors. [12]

Buying and selling land—the main source of colonial wealth—required multiple documents. In this greenbacks-starved economy, mortgages on land—and enslaved people—were a form of credit, forth with promissory notes, bonds, and lines of credit with merchants, payable through crops or appurtenances. If debtors defaulted, creditors needed litigation to access their assets. The duties on all these forms would increase the costs of routine legal transactions, especially for lawyers and merchants.[xiii]

Massachusetts Historical Society

Benjamin Franklin believed the Postage stamp Act "will affect the Printers more than Everyone," with duties on newspapers, advertisements, pamphlets, and almanacs.[14] In fact, it would affect all ranks of colonial society, from artisans who had to sign indentures with apprentices to tavern owners—many of them women—who had to obtain liquor licenses.[15]

The Stamp Act could also worsen weather condition for enslaved people in northern seaports. The mail-war depression and the Sugar Human activity had already resulted in a steep reduction in slave importations and the rise of slave sales.[xvi] Boston'southward enslaved population dropped from 1541 in 1752 (one-10th of the full population) to 811 in 1765.[17]

With these threats to the colonial economy in mind, colonists responded past publishing a deluge of pamphlets, resolutions, and newspaper articles. While pledging loyalty to King and Parliament, authors denied Thomas Whately's contention that American colonists "are about represented in Parliament," chosen for colonial unity, and asked for relief from the "extremely burthensome [burdensome] and grievous" postage stamp duties.[eighteen]

Violent Opposition to the Stamp Human activity

Another option existed also words of protestation. When the regime and laws did not serve the interests of the people, the people needed to correct those wrongs. A writer in the Boston Post-Male child and Advertiser captured colonial anger to the Postage stamp Human action when he asked:

Volition the cries of your despairing, dying Brethren be Music pleasing to your Ears? If so, go on! curve the Knee to your Master Horseleach, and beg a Share in the Pillage of your Country. [nineteen]

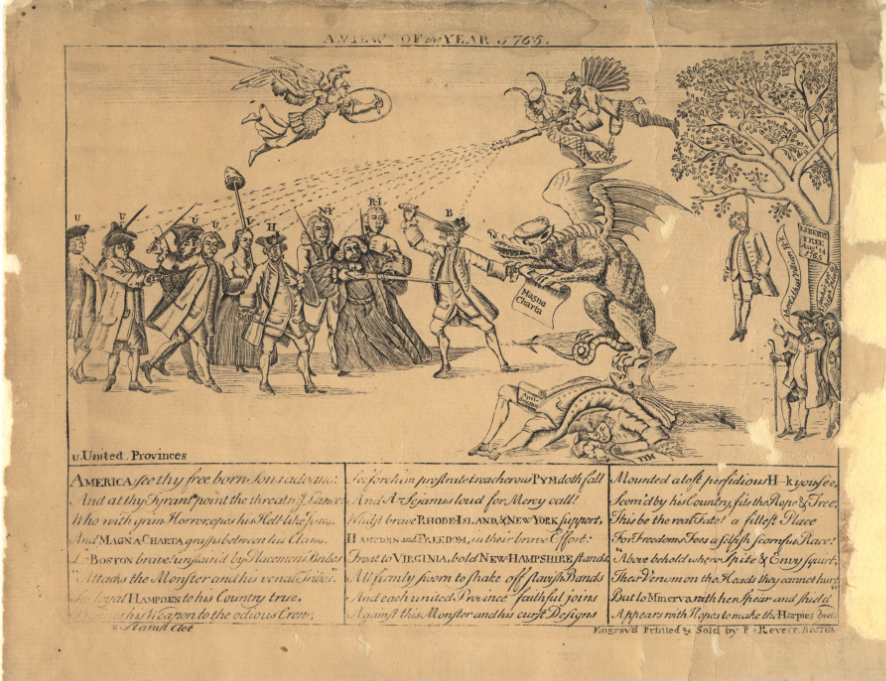

By early summer 1765, Boston's Loyal Nine began planning opposition to the Stamp Act. A group of middling men active in politics, the Loyal Nine included men such every bit John Avery, Jr., a merchant/distiller and Harvard graduate, and Benjamin Edes, printer of the Boston Gazette. James Otis and John and Samuel Adams probably knew nigh the Loyal Nine just had no official ties to the organization. The Loyal 9 prepared effigies of postage distributor Andrew Oliver and George III'south outset prime minister Lord Bute. They chose shoemaker Ebenezer McIntosh to execute their plan on August fourteen, 1765.[20]

McIntosh led xl-fifty artisans from the lower ranks, laborers, and mariners to carry the effigies through the streets and hang them from a large elm at Essex and Orange Streets (before long to be known as Freedom Tree).[21] The effigy of Bute, pronounced "boot," was a large kick with the Devil itch out. A label on Andrew Oliver's effigy warned: "He that takes this downwardly is an enemy to his country."[22]

At sunset, the group brought the effigies to Oliver'south dock, leveling a building they believed would exist the stamp office. Proceeding to Fort Hill, they burned the effigies, which should have concluded the protest. However, McIntosh and his less genteel followers connected with their own calendar. They headed to the dwelling house of postage collector Andrew Oliver, brother-in-police force to Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. They pulled downwardly Oliver's fences, bankrupt windows, destroyed piece of furniture, drank his wine, and stripped his copse of fruit. Twelve days later, they turned their protest to Hutchinson.[23]

James H. Stark, "The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution" (1907).

Protesting Hutchinson and the Postage Human activity

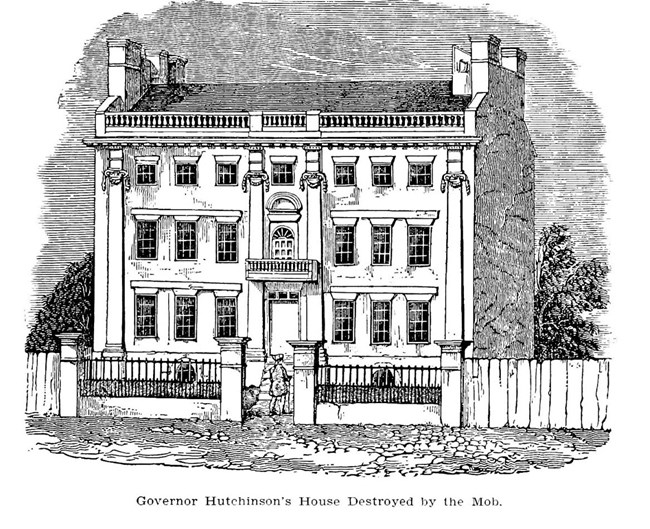

Ironically, Hutchinson agreed that Parliament had no ramble correct to laissez passer the Stamp Act and worked towards repeal. Simply the Boston mob remembered his long history of going against their interests: opposing paper money in the 1740s, trying to abolish the Boston Town Meeting in the 1760s, and simultaneously holding multiple political offices. In their eyes, Hutchinson earned money and status by serving King and Parliament at their expense.[24]

On August 26, 1765, McIntosh's mob first attacked the homes of William Story, deputy register of the Vice-Admiralty Court, and Benjamin Hallowell, comptroller of customs. Then, they unleashed their rage on Hutchinson. Home with his children, Hutchinson escaped with his life as the group avant-garde on his home. The mob destroyed furniture and tore out windows, partitions, wainscotting, roof tiles, and sawed off part of a cupola atop the mansion. They drank Hutchinson's wine, ruined his garden, stole £900 sterling, and damaged or destroyed thirty years' worth of books and papers collected for his history of Massachusetts. By the time they finished, in Hutchinson'due south words, "nothing Remained just blank walls and flooring."[25]

Even the most ardent haters of Hutchinson and the most ardent lovers of liberty condemned the attack. The Boston Gazette, published by the Loyal Ix's Benjamin Edes and his partner John Gill, warned that "the pulling down Houses and robbing Persons of their Substance…is utterly inconsistent with the first Principles of Government, and destructive of the Glorious Cause."[26]

Violence, intimidation, and a uncomplicated "word to the wise" directed at postage stamp distributors finer nullified the Stamp Human activity before it took outcome. I by one, twelve of the thirteen postage distributors for the colonies resigned before distributing stamps.[27]

Responding to this outcry of opposition, the colonies held a Postage stamp Act Congress in late October 1765 in a brandish of colonial unity. In their "Annunciation of Rights and Grievances," delegates stressed the importance of their trade to Britain, hinting that the "late acts of Parliament…will return them unable to purchase the articles of Great U.k.." An expansive non-importation movement, essentially a boycott of selected British manufactures, followed. Women played a pregnant role in this motion, as many women controlled household spending, owned businesses, and created a lot of the American-made goods colonists bought instead of imported goods. The success of the non-importation motility served as an important bargaining chip in achieving the Postage stamp Act's repeal.[28]

Repeal of the Stamp Human activity

The Postage stamp Act's repeal had to exercise more than with English politics than colonial activeness. In January 1766, British politician William Pitt emerged every bit the Parliamentary champion of the American colonists, upholding Parliament'south right to legislate for but non to tax the colonies. He called the Americans "the sons, non the bastards of England" and dismissed virtual representation as "the virtually contemptible idea that ever entered into the head of a human."[29]

When George III dismissed Grenville every bit prime minister in July 1765, the Marquis of Rockingham headed a coalition authorities. Caught between Pitt'due south defense force of the colonists and Grenville's defense of Parliament'due south unlimited authority over the colonies, the Marquis decided to appeal to both sides. The Stamp Human activity's repeal became combined with a Declaratory Human action that upheld Parliament'southward full say-so "to brand laws and statutes …to bind the colonies and people of America…in all cases whatsoever." Both laws passed on March xviii, 1766. The Declaratory Act passed unanimously; the Postage stamp Act repeal passed 275-167 in the House of Eatables and by a narrow majority of 34 votes in the House of Lords. Though the colonists had won their battle confronting the Stamp Act, they would soon come up to realize that the Declaratory Act held much wider power. But for now, the colonists rejoiced.[30]

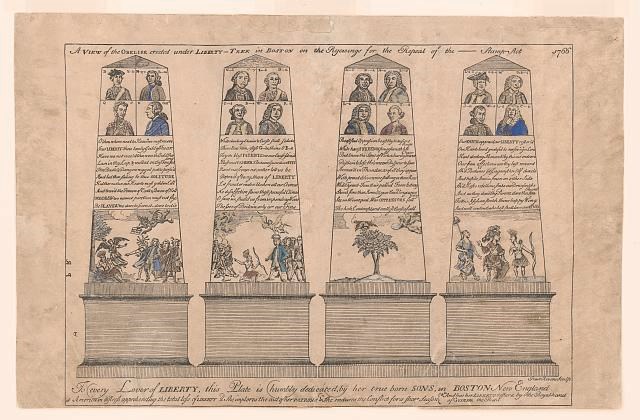

Library of Congress

News of the Postage stamp Act'southward repeal reached Boston on May 17, 1766: "the Bells in Town were set up a ringing…Guns were discharged…and in the Evening were several bonfires." Two days afterwards, the boondocks held a more stupendous celebration. The Sons of Liberty erected an obelisk in praise of liberty on Boston Mutual, described as "a magnificent Pyramid illuminated by two-hundred-and-eighty lamps." Paul Revere created an engraving of the obelisk to commemorate this symbol of liberty, which was destroyed by a burn during the celebrations.[31]

While the colonists accomplished victory in the repeal of the Stamp Human action, Parliament's enthusiastic credence of the Declaratory Human action imperiled colonial liberty and led both sides toward revolution.

Contributed by: Jayne East. Triber, Park Guide

Footnotes

[1] Boyle's Journal of Occurrences in Boston, 1759-1788, New England Historical and Genealogical Annals 84 (April 1930): 148-149 (on British victories in Quebec, 1759, and Montreal, 1760), 162 (on peace); Fred Anderson, A People's Army: Massachusetts Soldiers and Society in the Vii Years' War (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Printing, 1984), 22-23, on New England pride and quote from John Boyle'southward September sixteen, 1762, account of British victory in Havana.

[two] Jayne E. Triber, A Truthful Republican: The Life of Paul Revere (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), 37-40. Marc Egnal, A Mighty Empire: The Origins of the American Revolution (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1988), 126-135; Ed., Jack P. Greene, Colonies to Nation, 1763-1789: A Documentary History of the American Revolution (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 12-39.

[3] Massachusetts, New York, and Jamaica also passed postage stamp taxes in the mid-18th century. Edmund Southward and Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 3rd ed., 1995), 54; Lynne Oats and Pauline Sadler, "Bookkeeping for the Stamp Act Crisis," Bookkeeping Historians Journal, Vol. 35, Number ii (December 2008), 108-111; text of Postage Human activity https://avalon.police force.yale.edu/18th_century/stamp_act_1765.asp.

[4] Morgan, Postage stamp Human activity Crunch, 54-56 ; Lawrence Henry Gipson, The Coming of the American Revolution, 1763-1775 (New York: Harper and Row, 1954), 69-71; I. R. Christie, Crisis of Empire: Great United kingdom and the American Colonies, 1754-1783 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1966), 49-51.

[5] Morgan, Stamp Deed Crisis, 54-57; Christie, Crisis of Empire, 51-52.

[half-dozen] Christie, Crisis of Empire, 51-52, is more than charitable towards Grenville, writing that he "was willing to endeavour the possibility" that the colonies might tax themselves and obtaining prior consent from the colonies "might obviate ramble objections." Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 59-68, stresses that Grenville had Parliamentary approving to impose a Postage Act and then he did not need colonial consent. Quote on p. 68.

[7] Morgan, Stamp Deed Crunch, 65-68; Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Galloway, Oct 11, 1766, recalling the February ii, 1765, meeting with Grenville, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-13-02-0164#BNFN-01-13-02-0164-fn-0007.

[8] Morgan, Postage Act Crisis, 68-70; Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 79-80.

[9] Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, lxx-72; Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 80-81.

[10] Boyle's Journal of Occurrences in Boston, 84: 168.

[xi] Text of Postage stamp Act, https://avalon.police.yale.edu/18th_century/stamp_act_1765.asp; Whately, "The Lately Made Concerning the Colonies and the Taxes Imposed Upon Them…", https://web.archive.org/web/20050223013854/http://www.skidmore.edu/~tkuroda/gh322/Thomas%20Whately.htm; Christie, Crisis of Empire, 53-54; Gipson, Coming of the American Revolution, 79; Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 72-73. See manufactures in Harbottle Dorr Collection of Annotated Massachusetts Newspapers, 1765-1776, I: Apr-November, when the Postage Act went into effect. Articles, many of which contained responses from other colonies, continued until news of the Stamp Act's repeal in March 1766 reached the colonies, https://world wide web.masshist.org/dorr/.

[12] Daniel Dulany, "Considerations on the Proprietary of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies," https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/xGsBAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PP1, 24.

[13] Land purchases included documents for a land grant, a warrant to survey the property, and to annals the title. Justin DuRivage and Claire Priest, "The Stamp Act and the Political Origins of American Legal and Economic Institutions," Southern California Police Review 88 (2015), 875-912, especially 875-888, 898-912, https://southerncalifornialawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/88_875.pdf.

[14] Benjamin Franklin to David Hall, February 14, 1765, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-12-02-0029; Oats and Sadler, "Accounting for the Postage Act Crisis," 124.

[xv] DuRivage and Priest, Appendix, 906-912, lists the stamped documents and tax rate, demonstrating the broad impact of the Postage Deed, https://southerncalifornialawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/88_875.pdf. On artisans, come across Triber, A True Republican, 40-41. In the 1760s, women held 48.3% of tavern licenses in Charleston, South Carolina; 41.half dozen% in Boston, 24.four% in Philadelphia, and xv% in New York, in Benjamin 50.Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford and New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2007), 68.

[16] Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1979), 246-256, 320-321.

[17] On population, meet Lorenzo Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 84-85. On experience of the Black population, encounter Eric M. Hanson Plass, "So Succeeded by a Kind Providence": Communities of Color in Eighteenth Century Boston," M.A. Thesis, University of Massachusetts Boston, 2014, Figures 1 and ii, 58-59, 84; Robert Eastward. Desrochers, Jr., "Slave-For-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, v. LIX, no. 3 (July 2002), 654-664.

[18] On colonial response, see Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, Affiliate 7, and Greene, Colonies to Nation, 45-61. On representation run into, Whately, "The Lately Made Concerning the Colonies and the Taxes Imposed Upon Them…" https://web.archive.org/web/20050223013854/http://www.skidmore.edu/~tkuroda/gh322/Thomas%20Whately.htm. and Dulany, "Considerations on the Proprietary of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies," https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/xGsBAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PP1. On June 8, 1765, the Massachusetts House of Representatives issued a circular letter calling for colonial delegates to convene a Stamp Human activity Congress in New York the post-obit Oct. The quote on the "extremely burthensome and grievous" taxes is from "The Announcement of Rights and Grievances," written by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, and issued by the Postage Act Congress, discussed in Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 108-119.

[19] Boston Post-Boy and Advertiser, August 26, 1765, in Richard 50. Bushman, King and People in Provincial Massachusetts (Chapel Colina, University of Due north Carolina Press, 1985), 194.

[20] Morgan, Postage Act Crisis, 126-130; Nash, Urban Crucible, 292-293.

[21] Morgan, Postage stamp Act Crisis, 130, notes that there were "more than genteel members of the mob, bearded in trousers and jackets which marked a workingman."

[22] Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 126-130; Nash, Urban Crucible, 260-262, 292-293; Peter Shaw, American Patriots and the Rituals of Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard Academy Press, 1981), fifteen-xviii. Contemporary accounts in Boston Gazette, August 19 and September 16, 1765, Harbottle Dorr Collection, I: 166, 193, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/. Boyle's Periodical of Occurrences, August 14, 1765, 84: 169. Groundwork in Morgan, Stamp Human activity Crisis, 130-131.

[23] Contemporary accounts in Boston Gazette, August xix and September 16, 1765, Harbottle Dorr Drove, I: 166, 193, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/. Boyle's Periodical of Occurrences, August 14, 1765, 84: 169. Background in Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 130-131. For more than on the relationship between Revolutionary leaders and the "lower sort," come across Dirk Hoerder, "Boston Leaders and Boston Crowds, 1765-1775," in Ed., Alfred F. Young, The American Revolution: Explorations in the History of Radicalism (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Printing, 1976), 233-271.

[24] Nash, Urban Crucible, 226-227, 271-281; Bernard Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1974), 64-69.

[25] The all-time description is in Hutchinson'due south letter to Richard Jackson, August xxx, 1765, https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/2532#chsect1705. See also, Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, 131-134, Nash, Urban Crucible, 294.

[26] Boston Gazette, September ii, 1765, Harbottle Dorr Collection, I: 177, https://www.masshist.org/dorr/.

[27] Morgan, Stamp Act Crisis, Chapter nine ("Contagion and Resignations").

[28] Morgan, Postage Act Crisis, 107-119. On non-importation, which continued throughout the Revolutionary era, encounter Nash, Urban Crucible, 354-371, passim.

[29] Morgan, Postage stamp Act Crisis, Affiliate fifteen; Greene, Colonies to Nation, 65-66, 68-72.

[xxx] Greene, Colonies to Nation, 65-85; Christie, Crisis of Empire, 55-64.

[31] On celebration of repeal, Boston Gazette, May 19, 26 1766, Harbottle Dorr Collection I: 411, 412, 415.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/anger-and-opposition-to-the-stamp-act.htm

0 Response to "what was the significance of opposition to the stamp act?"

Post a Comment